DETROIT AFFINITIES: STEVE SHAW

Detroit Affinities: Steve Shaw is organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit and curated by Susanne Feld Hilberry Senior Curator at Large, Jens Hoffmann.

PAST EXHIBITIONS

DETROIT AFFINITIES:

STEVE SHAW

JANUARY 15 – APRIL 24, 2016

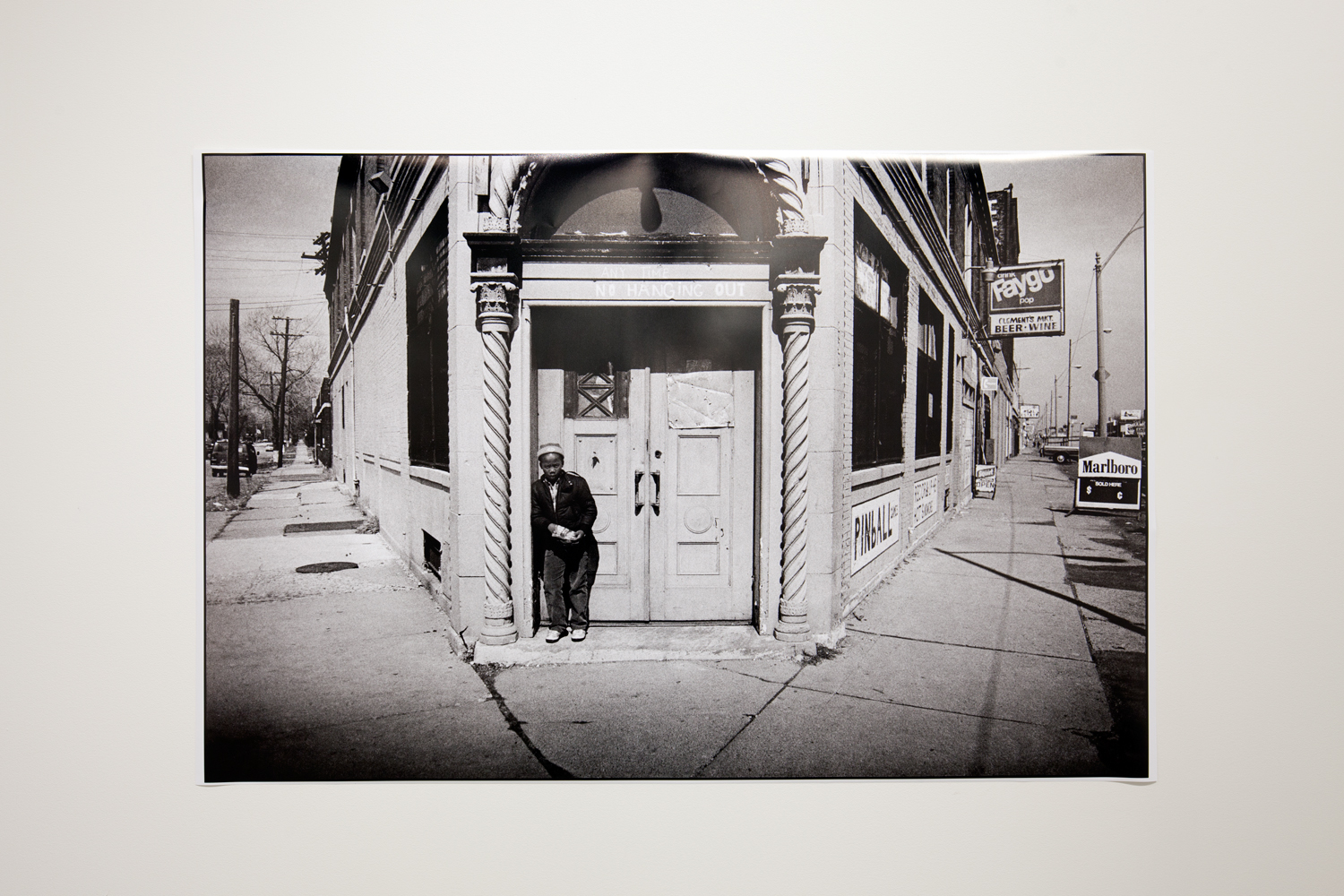

Steve Shaw completed one of his first photographic series just after high school, while working as a “ragpicker” at a Detroit factory. Though his job title had its own meaning at Motor City Wiping Cloth, the term typically refers to a person undertaking a kind of unauthorized labor in the street: collecting detritus to eke out a living. In a sense, this early role is a metaphor for the lifelong task Shaw assigned himself: to find value in the scraps and pieces of an urban scene that most people would throw away.

Over the past 100 years, United States cities have provided a wealth of content for social documentarians like Shaw. During the 1930s, Paul Strand chronicled the effects of the stock market crash where it happened, on Wall Street. In the 1950s, Robert Frank traveled across the country by car, recording life in cities from Miami Beach, Florida to Reno, Nevada. Lee Friedlander did the same in the 1990s and 2000s, capturing humorous idiosyncrasies at each stop through the car window and rear view mirror. Gary Winogrand distilled the riotous energy of 1960s Manhattan, while Diane Arbus archived its margins and subcultures. These photographers uncovered daily, lived joys and struggles by articulating their visual details: boarded-up windows and peeling paint, gleaming teeth and bruised flesh.

As a place where, in some sense, the Great Depression never ended, Detroit is a perfect setting for this kind of work. It is the home of the American automotive industry, and the symbolic center of its 2008 collapse. It is the city where a historic art institution was asked to contemplate selling its collection to help the city stay afloat in 2014, a harbinger of the ill effects of economic decline on arts and culture. Steve Shaw was born and raised here, and in his many years living and working in the city, he has found that it offers all the source material he needs.

Shaw grounds his practice in personal observation. He remembers the day he got his first camera (December 25, 1969, an Eastman Kodak Instamatic 44), and cites movies, television, family photos, and the pages of LIFE Magazine as early sources of inspiration. His images evidence an intimate point of view that comes from being enmeshed in a community. Even when he pictures strangers, his images lack the objective veneer of an outsider.

In Michigan Ave. Detroit (1983) a woman approaches in crisp focus, her face obscured by her umbrella. Directly above her is an array of competing signs, offering various metonyms of American vice: ammunition, auto parts, and alcohol. Blurred, though nearer to the lens, a neatly dressed man takes a small step toward an unknown storefront. Apart from these two figures, the street is empty. Our protagonists are alone in a vacant cityscape, where billboards vainly vie for attention above parked cars and industrial warehouses. In the foreground, a newspaper stand summarizes the subject of the image, in all its symbolic heft: USA Today.

This photograph bears witness to abstract phenomena by honing in on evocative details. In addition to the people it pictures, it gives form to diffuse concepts such as industrial ruin, economic decline, and the treachery of consumerism, which are otherwise too slippery to grasp. Because of their documentary quality, photographs like this have a unique kind of efficacy. They bring visibility to the details of life at and around the poverty line, and point up the contrast between the American dream and the reality of life with little money. As is the case in Michigan Ave. Detroit (1983), peripheral information is important in Shaw’s recent work. In Michigan Ave. Detroit (2014), he adopts an ancient trope—mother and child—but finds the pair at the intersection of Central and Michigan. The boy is riding a bicycle, and the woman walks with a plastic shopping bag and soda can in hand. Their contented facial expressions are a foil for the wrecked infrastructure around them: grass sprouts through cracks in the sidewalk, and a defunct Salvation Army thrift store is dark behind its barred windows.

Despite the dilapidated buildings that set the scene, such images are not without hope. In another new photograph, Gratiot Ave. Detroit (2014), a black couple sits low to the ground, flanked by signs of Obama-era optimism. Hovering above and behind them on a wall are hand-painted depictions of the President, First Lady, and a bald eagle; on their other side is an American flag. They appear to be waiting, but what they are waiting for is unclear. Shaw’s images form a collective portrait of Detroit—not only of its ongoing hardships, but also its insistent resilience, which can be spotted in an expression or stride. Like those of his predecessors, each of his photographs holds the city’s activity still. There is a kind of generosity in this visual quietude. It enables us to look closely for signs of endurance, and find them.

Detroit Affinities is organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit and curated by Susanne Feld Hilberry Senior Curator at Large, Jens Hoffmann. DETROIT CITY is comprised of three concurrent series: Detroit Affinities (exhibition), Detroit Speaks (education), and Detroit Stages (performance). This multi-year research program is one of the most ambitious undertakings to date at MOCAD.